The conundrum of monetary policy : A delicate balancing act

Share

BY NOW, it is of no surprise that the world has embarked on a global monetary policy tightening to counter inflationary pressures. Not only are central banks around the world on an ‘aggressive’ tightening path but the pace of tightening, globally is at its most rapid pace since the 2000’s (for the US, they have tightened at the fastest pace since 1994!). So yes, inflation has finally turned out to be a major worry (as Anneau had rightly anticipated since March 2020! – How, well everything was cooking up in this direction). From a risk management perspective, restarting the economic machine after months of lockdown was bound to create global supply chain disruptions and under supply, coupled with heated up private and public consumption (the massive US infrastructure bill adds to the commodity party boom as well). The extent of the damage however had not been priced in – War!).

This global tightening cycle is primarily to indeed contain inflationary pressures, which are invariably impoverishing, for the world’s poorest. How much and at what pace to tighten requires a lot of intellect and skills but also the proper monetary policy and their transmission tools. Balancing the considerations of economic growth and inflation is always an intellectual headache for Central Bankers and policymakers around the world.

Getting it right, however, takes much more.

As such, “Monetary policy is like juggling 6 balls… it is not ‘interest rate up, interest rate down’. There is the exchange rate, there are short-term yields, there is credit growth.” Raghuram Rajan.

Global rates rising fast: a monetary phenomenon

Since the past 3 months, we note that roughly 85 countries out of the 168 countries monitored have tightened their interest rates (by an average of 1%). The United States’ Federal Reserve has already hiked by 1.50% while the European Central Bank tightened by a surprising 0.50% in late July 2022 (for the first time in almost 12 years); thereby marking an end to this prolonged era of negative to low interest rates.

Elsewhere, Japan continues to stay put while China had to loosen its monetary policy by 10 basis points to 3.7% as the COVID-19 lockdowns and economic slowdown supported such a policy move. Brazil has already hiked 10 times since March 2021.

The developed and emerging economies are relatively massive as opposed to our domestic economy. The interest rate differentials and the pace of rates normalization domestically, however, remain worrying as we increasingly and ‘strangely’ lag.

Even the IMF now recommends urgent tightening

The IMF staff in its country consultation paper clearly recommends that (and we quote) “the BOM actively tightens the policy stance to control inflation and counter un-anchoring of inflation expectations and second-round effects: Inflation was already on the rise post-COVID due to supply chain bottlenecks, increasing transportation costs, and higher commodity prices. The war in Ukraine led to new pressures in the global commodity markets. This worsened the outlook for domestic inflation and increased the risk of un-anchoring inflation expectations and second-round effects if higher expectations are priced in nominal wages. A continued recovery may further increase domestic cost pressures.

Policy tightening does not need to wait for the roll-out of the new policy framework. While the new framework would allow for better management of interest rates, the BOM could deploy the existing framework in the interest of timely action.

It could mop up excess domestic cash reserves in full through the issue of BOM bills at a rate that induces the money market rate to align with the operational target (the announced policy rate).

The maturity of BOM bills could be reduced from 3 months to 7 days to make operations more effective. The pace of policy rate adjustment should depend on the macroeconomic and inflation outlook and aim to bring inflation back to its medium-term target over the monetary policy horizon.

“Increasing the announced policy rate and not fully transmitting it to the money market rate by means of open market operations will not suffice for tighter conditions.”

The BOM remains way behind the curve

We, at Anneau, have been hawkish since the past 2 years and in all humility, reiterate that the policymakers tighten as quickly as possible and to the tune of at least 50 basis points a month, such that the KRR (‘Key Repo Rate’) hits at least 4.25%.

With Q122 GDP growth having recovered to +8.7% (yes, low-base effect of Q121 and a commendable recovery in Food service & accommodation), the room for tightening is comfortably ‘ample’. Should inflationary pressures abate into the last quarter of the year (we already note that following the ‘Black Sea initiative’ agreement signed by Russia and Ukraine – to resume exports of grains and fertilizers, soft commodities prices have weakened by circa -21% since May 2022 – and we expect this weakness in global soft commodities prices to gather momentum into the end of year!), rates can be adjusted downwards, thereafter, as need be.

However, the longer our monetary policy tools are underutilized, we risk rendering the same tools sterile and the monetary transmission mechanisms are likely to grow increasingly inefficient – exacerbated by the weakness of the Central Bank’s balance sheet.

This supports the IMF’s views in this regard: “Consistent with the BOM Act, the government needs to cover the BOM’s losses which may materialize due to increasing policy implementation costs already in the near- to medium-term.

The BOM accounted the transfer to the government in 2021 as a dividend by exhausting the special reserves fund (SRF) of its accumulated valuation gains.

The BOM capital is relatively low at Rs10 billion (about 2 per cent of both GDP and BOM liabilities), which limits resources to sustain policy costs at higher interest rates and increased sterilization amounts.

In staff’s baseline projections, inflation normalizes by 2025 assuming policy is tightened appropriately. A key risk to the outlook is delayed or incomplete tightening. This may happen if the government signals. It also complicates the official reserve adequacy assessment unwillingness to increase the BOM’s capital and the BOM decides to limit expenses on domestic liquidity sterilization.6 Delayed tightening will inspire un-anchoring expectations and more inflation in the alternative scenario. Recapitalizing the BOM upfront is preferable to address the risk and create buffers in advance, but it is also more demanding for the fiscal sector.7 The Rs5 billion (1 per cent of GDP) in the BOM’s accounts receivable should not be transferred to the government to limit further deficit monetization.”

While we are cognizant of the quantum of imported (supply side) inflation via high global commodity & international freight prices, a historically weakened Rupee and domestic monetary policy’s vulnerability in addressing supply-side inflationary pressures, we stick to Milton Friedman’s “inflation is always a monetary phenomenon” and argue that demand and consumption needs to be tackled (and the only way to do so is via a much tighter monetary policy instance) and so the quantum and velocity of money shall be impacted in the manner so as to dampen consumption in the domestic economy; thereby helping it to cool off, in a controlled and disciplined manner.

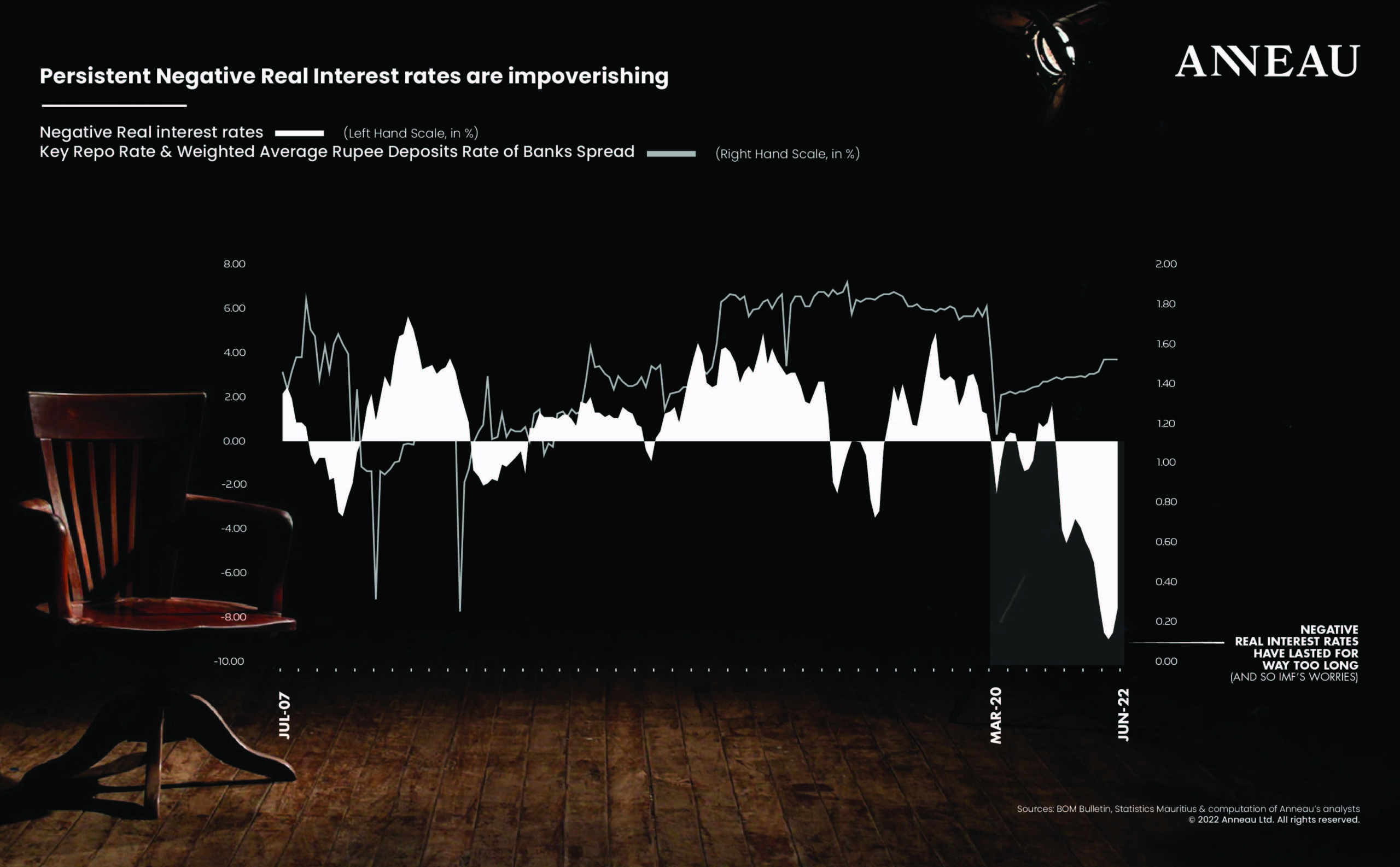

The longer negative real interest rates last, the more profound is the impoverishment

The Anneau graphic hereunder clearly depicts the worrying state of macroeconomic affairs of Mauritius and justifies why our nation has been impoverishing at the fastest pace that one can remember.

The chart not only contrasts the Key Repo Rate versus CPI inflation (Real interest rates on the RHS) but goes deeper into the Key Repo Rate and Weighted average Rupee Deposits Rate of Banks’ spread. One can hence clearly see and interpret the widening of the spread (and this despite a meagre +0.35% increase in interest rates by the Central Bank).

This negative real interest rates environment has lasted for way too long and needs to be reversed. The IMF does not expect (despite the high 2022 base in 2023) inflationary pressures abating until 2025 (we, at Anneau, are reasonably more optimistic for 2023 and 2024) and should this materialize and rates not normalized quickly enough in Mauritius, the impoverishment shall be even more profound and shall likely take years, if not decades to reverse (financially, the psychological impact and the poverty multiplier effects are other ramifications which are extremely difficult to ascertain but can be rightly so assumed – felt, by the most vulnerable).

The KRR / WARDRB spread clearly (and unfortunately) depicts that most domestic commercial banks are not adjusting their deposit rates (by extension savings rates) quick enough (on the contrary); yes, we do understand the excess liquidity issue (also highlighted by the IMF) and so the rates transmission mechanisms are not that effective, unless the commercial banks come to the party (unless the BOM should mop up as well (you do need a strong balance sheet for that!) and plays). Finally, it comes down to the regular ‘chicken and egg’ conundrum).

As such, the IMF states: “Effective policy implementation has been impaired by excess domestic liquidity and gaps in the system of instruments for reliable interest rate management, which becomes a more pressing issue now, when interest rate tightening is due. The BOM’s new policy framework design features an explicit inflation target and policy implementation based on the fixed-rate full-allotment, mid-corridor system and is in line with staff advice.”

They further recommend: “Tackling the legacies of the policy choices made during the COVID-19 pandemic, implementing modernized monetary policy framework, introducing an upgraded central bank legislation, and improving governance would help in this regard.”

Monetary intervention, without structural reforms; not a panacea

In addition, the Central Bank would need to step up its FX interventions (provided its balance sheet has been beefed up) but not only.

As the IMF states: “Some exchange rate adjustment has been allowed. However, the BOM continued substantial foreign exchange sales interventions and borrowed foreign currency to maintain official reserves. The rupee depreciated by about 10 per cent in nominal terms and 9 per cent in real effective terms in 2021. While FX interventions primarily aimed at clearing the market, there is scope to let the exchange rate adjust more flexibly to achieve warranted external adjustment. The BOM’s total FX sales to banks and the STC increased to US$1.5 billion in 2021 compared to about US$1 billion in 2020, reflecting market supply shortage amidst the large current account deficit.

At the same time, the BOM borrowed from non-residents and accumulated FX deposits of domestic banks, the sum of which exceeded the volume of FX sales interventions and subsequently led to an increase in its foreign assets. Gross official reserves increased to US$8.5 billion (almost 22 months of imports) by end-2021 compared to US$7.2 billion at end-2020.

Increasing FX obligations to maintain the level of official reserves exposes the BOM to the risk of reversal of volatile FX domestic deposits: banks’ withdrawal of such FX deposits contributed to a decline of official reserves to US$7.3 billion by end-April 2022.”

In an analytical note published by the IMF in April 2022 on the ‘role of foreign exchange intervention in SSA’s Policy toolkit’:

“This new analytical framework considers the combined and potentially interacting role of monetary, exchange rate, macroprudential, and capital flow management policies…

![]() This analysis finds that intervention may indeed have a constructive role to play in the policy toolkit for sub-Saharan African countries, but this must be weighed carefully, given the region’s complicated policy environment. Indeed, for most countries, the case for or against intervention is far from straightforward. Shallow markets, weak monetary policy credibility, and high FX liabilities are common features throughout the region, implying that large exchange rate movements risk de-anchoring inflation expectations and can pose risks to financial stability. In such circumstances, exchange rate flexibility may act as a shock amplifier instead of a shock absorber… Policymakers should also avoid FX sales that risk eroding reserve adequacy and use episodes of positive market sentiment to shore up buffers.”

This analysis finds that intervention may indeed have a constructive role to play in the policy toolkit for sub-Saharan African countries, but this must be weighed carefully, given the region’s complicated policy environment. Indeed, for most countries, the case for or against intervention is far from straightforward. Shallow markets, weak monetary policy credibility, and high FX liabilities are common features throughout the region, implying that large exchange rate movements risk de-anchoring inflation expectations and can pose risks to financial stability. In such circumstances, exchange rate flexibility may act as a shock amplifier instead of a shock absorber… Policymakers should also avoid FX sales that risk eroding reserve adequacy and use episodes of positive market sentiment to shore up buffers.”

Economic growth vs inflation

While the US has downgraded its 2022 GDP growth forecasts from 2.8% to 1.7%, Europe by -1.1% (primarily on the Russian / Ukrainian conflict), we expect the same globally speaking (as anticipated earlier during the year, the tighter monetary conditions domestically shall slow the economic machine by year end! Thereby leading to much weaker global commodity prices and tighter inflationary pressures) as the Global GDP growth has been revised downwards to +3.6% in 2022 (and 2023).

Should over monetary policy tightening (as opposed to under tightening) create sustained pressure on growth, we may as well risk seeing a recession by Q322, but numbers are likely to pick up strongly by the last festive quarter (especially the first post-pandemic Christmas consumption momentum is likely to be materially higher, year on year).

In line with this global trend, we expect GDP growth to hover around 5,3 % in 2022 as the economy recovers. Notwithstanding tightening, we could well hover near the sixes (with a clear cooling off in 2023), but this, in our humble opinion, remains on the higher end of the curve.

The balancing act is a major worry of all notable central bankers around the world. Either they under or over tighten (which is understandable).

However, in the face of the most ferocious impoverishment of our nation since independence, the question of not using available monetary pools should not even be on the table (especially in a strong economic recovery year).

“Increasingly, the domestic stock market is pricing in this policy mismatch, a rise in credit defaults and weaker consumption. The longer inadequate monetary policy lasts, the poorer, shall our people become”.

ANNEAU

Anneau is a financial services company licensed and regulated by the Financial Services Commission (‘FSC’) in Mauritius.

Phone : 2141717

Website : www.anneau.co